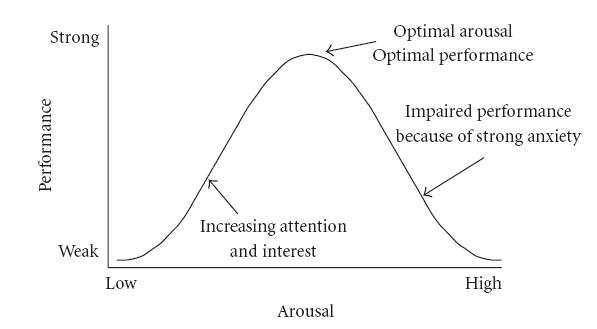

In the 1930s endocrinologist Hans Selye differentiated between two types of stress, distress and eustress. We are all familiar with the first term but perhaps less with the second term which refers to a positive response to external stressors leading to a state of optimism, confidence and agency, in other words ‘good stress.’ The origins of this model has its roots in 1908 when psychologists Robert M. Yerkes and John Dillingham Dodson posited that productivity is directly correlated with an optimal state of stress. Too little of it and you get nothing done, too much of it and you get nothing done either.

A key concern of anyone working in education is monitoring the stress levels of staff and students. Of course we don’t want anyone to be in a state of distress but we now live in an age that often views all stress as distress without acknowledging the benefits of eustress. Is it possible to imagine a more ‘stress-tolerant’ culture where students embrace a ‘sweet spot’ or optimal level of stress, one where we could engender a atmosphere of positive challenge and agency? As Ben Martynoga points out:

This is where good teachers and managers should push their charges: to the sweet spot that separates predictable tedium from chaotic overload. Where stress gets more persistent, unmanageable and damaging, Selye calls it “distress”. Eustress and distress have identical biological bases; they are simply found at different points on the same curve.

The key point here is that both of these states are responses to external stressors as opposed to being caused by events themselves, in other words, perception is everything. A key question here is in what way do educators shape the perception that all stress is distress?

Broadly there are two responses to stress, an initial avoidance and then subsequent coping strategies. For a group of Yale researchers, both of these approaches deny the benefits of eustress because they perpetuate the idea that all stress is bad:

These approaches advocate and perpetuate the mindset that stress-is-debilitating, a mindset that not only is partly inaccurate but may also be counter-effective. Even hardiness and resilience approaches to stress, while acknowledging the enhancing outcomes, still ultimately affirm the mindset that the debilitating effects of stress must be managed or avoided.

In contrast to the “stress-is-debilitating” mindset, these researchers discovered that students could be primed to adopt a “stress-is-enhancing” mindset in which they embraced a certain level of stress and which resulted in them being more open to seeking help, more open to feedback, which led to lower levels of distress overall and which had “positive consequences relating to improved health and work performance.” This “stress-is-enhancing” mindset has many resonances with Robert Bjork’s notion of desirable difficulties.

We are all familiar with the”stress-is-debilitating” mindset. When we have open ended large tasks, we are often are on the left of the Yerkes-Dodson curve, with little or no stress and thus no stimulation to act, but when the deadline is looming, we find ourselves often on the right of that curve, in a state of paralysis, unable to act and making poor decisions in an effort to alleviate the distress. Clearly then the ‘sweet spot’ is to be in a state of eustress, characterised by hope, excitement, active engagement, (O Sullivan, 2010) and that feeling that you are in control of the task you are faced with.

While there are some serious external stressors that are debilitating no matter what your response to them, two questions worth asking are:

- Are the kinds of tasks we are asking students to do genuinely placing them in a state of distress or could they be seen more positively as a potential state of eustress?

- Are we focusing on teaching methods that actually increase distress such as a focus on the storing of information as opposed to the retrieval of it?

In education research there is often very little consensus, but one area in which there is almost unanimous agreement is in the testing effect. We now know that the worst thing we can advise students to do in terms of revision is to re-read material and highlight key points, and that the most effective thing we can advise them to do is to practice retrieving information through testing, preferable through self testing, low stakes quizzing and flash cards. This distinction between storage and retrieval processes is well researched as Roediger and Butler explain:

“The testing effect is a robust phenomenon: The basic finding has been replicated over a hundred times and its generalizability is well established.”

So we know that testing is beneficial for learning but yet the general perception of testing seems to be altogether negative. Is the problem not just the high stakes nature of them but also how students are prepared for them? If students are using poor study techniques like re-reading and highlighting material for most of the school year within a curriculum that is not interleaved but focuses on mass practice, is it any wonder that they enter a state of distress when they enter exam season?

Stress experienced early in life can be debilitating and potentially devastating if compounded throughout life. Where children experience prolonged periods of distress they need the proper help and support to enable them to cope and we clearly have some way to go in this area. But are the kinds of tasks that we are asking them to do in schools genuinely creating a state of distress? If stress is a often a question of perception as Selye claimed then to what extent is it helpful to portray testing and exams for example as a key contributor to a “mental health crisis spiralling out of control?”

Stress is a very difficult area because it is highly subjective and often results in emotional and sometimes irrational reactions to it. We all want to create a healthy, productive atmosphere for staff and students in which they feel they have agency over their future and in which they don’t feel overwhelmed by external stressors but by viewing all stress as distress without harnessing the hidden benefits of eustress, we might just be missing a trick.

– Diamond DM, et al. (2007). “The Temporal Dynamics Model of Emotional Memory Processing: A Synthesis on the Neurobiological Basis of Stress-Induced Amnesia, Flashbulb and Traumatic Memories, and the Yerkes-Dodson Law”. Neural Plasticity: 33. doi:10.1155/2007/60803. PMID 17641736.

O’Sullivan, Geraldine (18 July 2010). “The Relationship Between Hope, Eustress, Self-Efficacy, and Life Satisfaction Among Undergraduates”. Social Indicators Research 101 (1): 155–172. doi:10.1007/s11205-010-9662-z.

Roediger & Butler Encyclopedia of the Mind (2013)

Rethinking Stress: The Role of Mindsets in Determining the Stress Response

Leave a comment