In 1846 the general hospital in Vienna was experiencing a peculiar problem. There were two maternity wards at the hospital but at the first clinic, infant mortality rate was around 16% while at the second clinic the rate was much lower, often below 4%. Mysteriously there were no apparent differences between the two clinics to account for this.

Part of the mystery was that there was no mystery. Almost all of the deaths were due to puerperal (childbed) fever, a common cause of death in the 18th century. This fact was well known outside the hospital and many expectant mothers begged to be taken to the second clinic instead of the first. The stigma around the first clinic was so great that many mothers preferred to give birth in the street than be taken there.

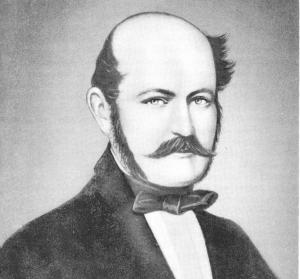

Working at the hospital at the time was Ignaz Semmelweis, a young doctor who had risen to the ranks of assistant professor where his duties included the examining patients before the professor’s rounds. Perturbed by the seemingly unsolvable nature of this mystery, young Ignaz recorded that it made him “so miserable that life seemed worthless” and so dedicated himself to finding a solution.

The breakthrough came when his close friend and colleague Jakob Kolletschka died of the same infection after cutting himself with a surgeons scalpel during an operation. Semmelweis then noticed that in the first clinic doctors were routinely conducting autopsies whilst in the second this practice did not occur. He also noticed that doctors were often delivering babies and treating patients with the same unwashed hands they were performing autopsies with and so proposed that doctors were contaminating patients with “cadaverous particles.” He then insisted doctors wash their hands in a chlorinated lime solution before dealing with patients resulting in a drop in deaths from puerperal fever to around 1%.

However despite this transformative discovery many in the medical community at the time were not only skeptical of Semmelweis’s findings but openly mocked them. Charles Meigs, a prominent American obstetrician (and teacher) derided the notion of bacterial infection and antiseptic policy noting that “Doctors are gentlemen, and gentlemen’s hands are clean” and that any that it was morally unacceptable to “contravene the operations of those natural and physiological forces that the Divinity has ordained us to enjoy or to suffer.” Even when Semmelweis published his findings, he still came up against intransigence and entrenched partisanship. August Breisky, an obstetrician in Prague, referred to his work as “the Koran of puerperal theology.”

This reactionary short-sightedness gave rise to the the term The Semmelweis Reflex: “the reflex-like tendency to reject new evidence or new knowledge because it contradicts established norms, beliefs or paradigms.” Now education is clearly very different from medical practice, but there are things we are discovering about the process of learning that the profession can no longer afford to ignore. In the last 10 years we have witnessed an explosion in what we know about the essential dynamic of how the brain retrieves and stores information. The field of neuroscience in particular has afforded huge opportunities to the profession by challenging and clarifying erroneous beliefs through not just solid evidence, but important evidence yet still many many of these problematic ideas are still widespread.

We now know for example that left and right brain thinking is not supported by any evidence, we know that the belief in learning styles is not just wrong but dangerous, we know that the claim that we only use 10% of our brain is completely unfounded and that if you are using Neuro linguistic programming for education purposes then you might as well be practising astrology. Yet despite these important findings, may of these beliefs still persist in education settings today.

Against this clearing out period of debunking and myth-busting, we have also had a number of significant discoveries such as Sarah Jayne-Blakemore’s work on the teenage brain and the fact that “disorders like anxiety disorders, depression, addictions, eating disorders, almost all of them will have their onset some time during the teenage years.” Her work proposes to explore how “genes and the environment influence brain development, like for example, how adolescent brain development differs between cultures is something that no one has yet asked, and yet it’s bound to.” These issues and the potential findings from them seem to be not only integral to the practice of teaching children but also ethically imperative. Yet how much of these findings are properly embraced by the profession in a way that is commensurate with other professional fields?

Even where important ideas have been adopted, implementation of them has been problematic. Dylan Wiliam’s work on assessment for learning from 1998 is a seminal contribution to the field of education research but has used reductively to simply mean kids knowing what level they are working at or teachers sub-levelling individual pieces of work. These issues raise some important questions:

Whole School Cognitive Dissonance: What is the value in a school preaching Growth Mindsets in an assembly yet basing their entire school enterprise on the reductive and fixed mode of target grades and narrow assessment measures based on poor data? Why are kids explicitly told that their brain is malleable but implicitly told their target grades are not?

Insufficient training: Why are teacher training courses essentially a mad trolley dash around hugely complex ideas over 8 months, where trainees spend more time collating paperwork against often arbitrary targets than engaging with significant research? (I don’t blame PGCE providers for this – they are working in an increasingly difficult area with less and less resources but where did the idea come that you could learn all you need to know about teaching and be classroom-ready in less than a year?)

If not evidence then what? If educators are not interested in evidence then what are we actually talking about? Are we basing our entire professional practice solely on our own experience in the classroom 10 or 20 years ago? Or should our professional judgement be one that is informed by and that engages with a wider body of knowledge from different disciplines? Are we so arrogant to think we have nothing to learn from different fields?

Ethical considerations: If research shows us that certain practices lack any evidence or are ultimately a waste of time, is it ethically right that teachers continue to use these practices? As mentioned, learning styles has been fairly widely debunked now but why does it continue to linger in so many educational arenas? And what are the implications of new research for educational monoliths like group-work, differentiation, Bloom’s taxonomy and traditional marking?

Three of the most important aspects of teacher development are trust, professional judgement and autonomy but surely that judgement and autonomy is only enhanced and not hindered by new findings about how learning takes place. As with Semmelweis’s detractors we shouldn’t be rejecting new ideas and discoveries, especially ones that are so relevant to our field but rather incorporating them into our own practice. One of the challenges to education research is the perceived threat of “evidence” as an axiomatic truth to be delivered on high that will limit teacher autonomy and agency in the classroom but I for one am excited by education incorporating these new findings around memory, retention and performance and incorporating them into their own professional practice and then making them applicable in the classroom where they can have the most impact.

Neuroscience and Education: Issues and Opportunities – ESRC

Neuroscience: implications for education and lifelong learning

Why the Widespread Belief in ‘Learning Styles’ Is Not Just Wrong; It’s Also Dangerous

Leave a comment